the good fight

generative AI, jimmy carter, instapoetry, and weird tech guys with dad holes

Somewhere between the valley of doom-scroll fatigue and the peak frustration of having to endure the ritualistic humiliations of capitalism, I dash away my overflowing folder of apparently unimpressive Curriculum Vitaes and prostrating cover letters, open up a new Text Post (yes, I’m one of those psychos who write directly into the Substack drafts—when life has no edge, whetstone your own) and make the decision to bravely cover ground I’ve not yet trodden before.

That’s right, darlings. I’m finally tackling ✨Artificial Intelligence✨.

At first, I dream of a go-to guide on AI resistance—a coruscating analysis so thorough that, if you squint, you’d mistake it for a sassy PhD paper. I start writing. The dream becomes misshapen. Its too stiff, it sounds preachy, its tedious to write and even more boring to recite back. The draft transforms, implodes, evolves. The intention to explore the concerns of, and around, this technology remain.

It’s difficult to talk about Artificial Intelligence when it’s building its own hull mid-flight. Criticism of an emergent technology requires figuring out how to criticise it—which involves working backwards from the visceral instinct and shaping its raw material into something refined. When it comes to AI, I trust my intuition. It tells me to not be fooled, to be wary, to resist, speaking at a volume much louder than the usual paranoia that basically utters the same kind of things, only quieter and about more absurd shit, like the old white lady in Tesco who looked me dead in the eye before tilting her shopping trolley to a 90-degree angle in the middle of the aisle, trundling off to pick up some Le Rustique Pasteurised Camembert from another shelf. I know you saw me coming, Glenda.

I’d rather not repackage my intuition and present it as “balanced” in pursuit of a journalistic standard that pretends neutrality is the highest form of intellect—so high, in fact, that nary a mainstream news outlet in the western hemisphere can complete a muscle-up to call a genocide by its name. Thus, I abandoned the dream of a comprehensive go-to guide.

Instead, I crafted a GPS route (because traditional maps are cartographically obsolete and everything outdated deserves a vicious, peasant’s death) to document a wandering.

Follow along, if you want.

Picture me: hunched over laptop keys.

Eviscerating, technophobic take-downs seep from my finger-tips with a viscosity that is, quite frankly, gross to the point of sensual intrigue.

I’m riffing on a level that is frickin’ sublime. Until I’m undone by a stray Google search that coldly and callously sets in motion a chain of events which end with me realising I’ve been mistaking Generative AI for Artificial General Intelligence.

Yikes.

I backspace 2000 words in blind fury. Here I am, thinking the Ayahuasca-addled, Great Automatic Grammatizator of ChatGPT is four OpenAI updates away from gaining sentience and plugging us all into the Matrix. I’d lapped up the shiny, chrome Kool-Aid. A faux pas destined to haunt me as ghoulishly as the time I loudly mispronounced a word I’d only ever seen written in a room full of my literary peers at one of the most prestigious libraries in Britain.

I’ve been saying “high-per-bowl” for like, two decades. Oh, well.

In case you’ve been messing up, too: Generative AI uses deep learning to specialise in a complex but single task—making them narrow artificial intelligences. Some also call them “weak artificial intelligences” but I’d rather not have too many robophobic comments in my digital archives when the techno-pocalypse begins. You think the backlash against white celebrities’ circa 2012 tweets was bad? Wait until our future robot C.E.Overlords dig up your old “clanker” jokes.

Anyway, Large Language Models, Text-to-Video Models, Text-to-Image Models, Text-to-Music generation are all examples of narrow artificial intelligence. The most popular and widely accessed Generative AI is, of course, Chat-GPT. Its task is to pull from vast datasets of text to generate humanlike responses to input queries. It does this task pretty well—but it sucks at maths. ChatGPT couldn’t tie its own shoelaces if you screwdrove robot hands to its servers. And it’s probably not going to win any Go championships any time soon.

There is so much stuff about Generative AI floating in the necrotic vastness of cyberspace.

AI’s getting more powerful but its “hallucinations” are getting worse.

Humans are falling in love with prompt machines.

Claude Opus 4 might resort to blackmail to stay alive.

Anybody want to create a NSFW chat-bot girlfriend?

Facial recognition policing seems pretty dystopian.

Generated babies videos, that feels pretty spooky.

A teenager killed himself earlier this year after months of encouragement by Chat-GPT.

Learning literally anything about Palantir1.

Separating the reasonable risk from the moral panic or the valid benefits from capitulatory glazing was a dizzying exercise that, honestly, would’ve made a go-to guide come out pretty shit. Luckily I’m not doing that any more. I still think Artificial Intelligence, especially the Generative persuasion, is a pretty bad idea.

In the anthropocene—the era where mankind has, in our impressively short lifespan on the face of the earth, had the biggest hand in fucking it up—humanity has caused:

Air, Water, and Light Pollution

Britain kicked off the industrial revolution, setting the pace for America to take the rootin’, tootin’ pollution baton and digivolve into a superpower. There was a glimmer of hope, maybe, once. A brief period where environmental consciousness was an institutional focus in a presidential administration. Jimmy Carter established the Department of Energy in 1977, set goals to shore up renewable energy, regulated strip mining and even installed solar panels on the The White House roof. As far as being in charge of a hyper-militarised, cowboy capitalist settler-colony built on slavery with an insatiable lust for instigating foreign coup d'états, Jimmy seemed like a pretty decent bloke2.

I guess the American public thought he was a hippie loser who was too soft on the Ay-rabs or whatever—so they voted him out. I probably needn’t say more than Ronald Reagan removed the solar panels in 1986.

Industrialised nations have gone on to pave a global ecosystem over the natural world. You read studies reporting half of world’s CO2 emissions comes from 36 fossil fuel firms, concentrating pent-up rage at the big, bad, ultimately faceless energy companies. We know the biggest culprits, just as we know tearing down those 36 firms, shutting down plastic production or turning off every oil refinery on the planet would destabilise our precious ecosystem (which is totally the best system that’s ever existed) in a way nobody is willing to deal with. Imagining a new world is one thing, bringing it into fruition is another.

You and I may never have a carbon footprint as big as an oil baron but we’re complicit by way of citizenship of the western world. And it sucks. A lot of bisonshit being done in our name and with our tax pennies. Trivial (or fraudulent) initiatives help us believe meaningful change is happening, as if the inconvenience of drinking through paper straws at Wagamama’s or manoeuvring our mouths around bottle-lid attachments are finally turning the tide in the war against pollution. Tell that to the micro-plastics in my amygdala, every raindrop on the planet being contaminated with forever chemicals or the garbage island the size of Angola floating in the North Pacific.

Everything about the way we’re living as a civilisation is so clearly unsustainable and it seems vaster and more interconnected than we can wrap our palaeolithic minds around. There’s little anyone feels they can do about it individually because if my next-door neighbour isn’t giving up beef to save the Amazon rainforest then why the hell should I deprive myself of a cheeky Marks and Sparks Wagyu steak?

Companies that bleed and burn the world’s fossil fuels are seen as “lawful” because the greenhouse gasses they pump into the air are within “acceptable legal limits” while climate activists are routinely punished under the same rule of law. A bunch of countries signed that Paris Agreement like, a decade ago. That was cool. Can’t help but feel like the government I have the displeasure of living under takes the agreement less seriously than they take the French themselves, though. Seems like they’re more wrapped up in the brave work of berating and criminalising asylum seekers as a spineless capitulation to the rising far-right in this country.

I get it. After 20+ years of whipping the white working class into a rabid islamophobic fugue state, it’s probably easier to dabble in perception management than try to avert the slow-motion car-crash of societal collapse. It’s just toooo difficult to tax über-rich guys, treat war-fleeing asylum seekers with some basic human dignity and transition towards sustainability before we’re all smoked by hydrofluorocarbons.

…This is the cultural context Generative AI is spawning into.

One of the more widely studied impacts of Generative AI is its energy use.

Each time a model is used, perhaps by an individual asking ChatGPT to summarize an email, the computing hardware that performs those operations consumes energy. Researchers have estimated that a ChatGPT query consumes about five times more electricity than a simple web search.3

Alphabet Inc’s CEO John Hennessy often gets cited when speaking about the energy expense of LLM’s, claiming they “likely cost 10 times more than a standard keyword search.” Andy Masley points out that a single ChatGPT prompt only uses 3 Watt-hours—equivalent to running a vacuum cleaner for 10 seconds or playing a games console for a minute.

If you multiply an extremely small value by 10, it can still be so small that it shouldn’t factor into your decisions. If you were being billed $0.0005 per month for energy for an activity, and then suddenly it began to cost $0.005 per month, how much would that change your plans?”4

The MIT Technology Review crunched the numbers of AI’s energy usage. I’m only half-concerned with the statistics themselves. The figures for energy usage (or water consumption) are fundamentally flawed abstractions. The consequences of the data they represent are too far removed from our immediate experiences. When I mentioned abstaining from eating beef, do you think you would’ve thought about the Amazon Rainforest unless I mentioned it explicitly?

When it comes to environment, we rely on translations to make us care. Harm presented as numerical data, verified reports of collapsing environments, photographic evidence of decaying habitats. I don’t think you need them. Because you feel it, don’t you? The friction between capitalistic growth and ecological sustainability, its thermal contradiction contorting your mind and cracking the planet like an eggshell. Food doesn’t taste as flavourful any more. There’s way less bugs in the summer. The last few European heatwaves straight up caused thousands of heat deaths. Academic papers and copious links in a Substack essays don’t need to convince you.

You can feel it.

Environmental critiques of Generative AI should be a discussion-ending mic-drop but we’re so culturally avoidant about nature’s destruction that any pollution Generative AI causes is too easily rationalised as inconsequential. Its just more, unremarkable wood for the raging bonfire that’s already suffocating us all.

Generative AI isn’t uniquely polluting. Masley’s claim that Chat-GPT isn’t bad for the environment isn’t a calculus of harm, more a declaration of conformity saying: The damage isn’t that bad when you compare it to the damage that’s already going on. In a way, these kinds of essays are initiation processes—welcoming Generative AI into the apathetic norm.

Perhaps then—it is more useful to speak about what will, rather than what is. If Generative AI is to become a societal mainstay (and I suspect it’ll have more enduring relevancy than the equally environmentally unfriendly ancestor of NFT’s) the demands of its existence will come at a great cost to the world.

Those costs will mount—environmentally, financially and, fuck it, existentially—blending into the expenses we’re already spending, hiding in plain sight until we can no longer live in denial about their impact.

In Britain alone, data centre usage is expected to “surge six-fold in 10 years”. There’s no way on God’s rapidly-browning Earth that uptick will be handled greenly. At best, the data centres will comply with current energy regulations—keeping the civilisational ship steady on its course towards a slowly melting iceberg. At worst, high demand will lead to aggressive expansions and data centres like Elon Musk’s that are currently poisoning Memphis will become far more common. At a certain point, we have to ask whether the technological advancements bringing comfort to our lives are worth the breath they’re stealing from our sky and what we’re going to do about it.

Gary Stevenson was a Citibank trader, securing major successes in finance by betting on the collapse of the economy. He left it all to write a book and run a Youtube channel calling for the UK government to tax the rich.

Stevenson breaks down how the wealthy have been capitalising from economic events like austerity, COVID bailouts and the housing crisis with focused concision. His videos are like Promethean fire on these bleak abysmal isles. Boy, is it dark-sided round here. At the top of the year, Oxfam reported, “Britain has highest proportion of billionaire wealth derived from monopolies and cronyism among G7 countries.” According to the Economic Policy Institute, CEO’s in 2023 were paid “290 times as much as a typical worker—in contrast to 1965, when they were paid 21 times as much as a typical worker.” America

Stevenson’s videos and public appearances warn, urgently, that if the unchecked greed of corporatism isn’t met with intervention the resulting economic decline will plunge large portions of the population into poverty. We are careening towards neofeudal levels of wealth divides and it’s clear that Generative AI is one of architectural instruments being used to accelerate this transmission of wealth:

“CEOs are extremely excited about the opportunities that AI brings. As a CEO myself, I can tell you, I’m extremely excited about it. I’ve laid off employees myself because of AI. AI doesn’t go on strike. It doesn’t ask for a pay raise. These things that you don’t have to deal with as a CEO.” — Elijah Clark5

Entry level jobs are disappearing. OpenAI themselves declared the roll-out of Chat-GPT 5 is “a major step towards placing intelligence at the center of every business.”6 Worker replacement has already begun. In the US, there is currently more unemployment than job openings. People are getting replaced and the entity does a shittier job than them.

Recently, when watching Burnt (2015) on Amazon Prime, the captions had translation errors similar to Tiktok videos and Instagram Reels. There were three different misspellings of “tarragon” because three different people said it in three different accents. A professional captioner wouldn’t have made that mistake. It was clear Amazon Prime had begun using AI to caption their films and TV shows.

Y’know—If I could do one thing to dam the virulent spread of anti-intellectualism, it’d be blow-darting the knowledge into everyone’s brains that “X is the New Y” statements are not impressive in 2025. The most insufferable sapiosexual you know is spewing out some fake-deep word equation like “AI is the new printing press” and the similarities are so surface level that it’d only be a lightbulb moment for someone so dim they need Chat-GPT to--You know what? Too mean. I’m trying to abstain from the holier-than-thou supposition that Generative AI is an inherent, intellectual failing and I’ve grown a little uncomfortable with the “Chat-GPT depletes critical thinking” quips. They’re getting a little eugenicsy, if you ask me.

But I don’t know, man. The printing press made scribes and scriveners obsolete by democratising the mass-production of books. Generative AI is transactional—you prompt what you want and it echoes those wants back to you. The process of creativity is outsourced and, ultimately, forfeited. Artistically, it’s creative middle management.

Any resemblance AI has to the printing press begins and ends at the point of it being a popular, new technology—which you could just as easily compare to the home printer or mobile phones. If we’re going to whip up cringy snowclones, I’d personally go with “AI is the new cotton mill” seeing as the debut of the textile factory was met with infamous animosity. Retrospect implores us to see the comforts of today through a sort of teleological-capitalist lens—we look around and see iPads, flat-screens and Teslas and we infer they’re optimally designed.

Deeper investigation shows the Luddite movement was fighting to preserve standards of living we’d be lucky to have today. Their Cottage Industry was the OG Work From Home. Cloth-makers wanted the autonomy to continue earning wages that didn’t depend on working under someone else’s roof. When peaceful protests and appeals to government were denied, the cloth-makers earned the Luddite moniker by sabotaging the cotton mill machinery.

History has downplayed Luddism as a neanderthal tantrum or superstitious moral panic. It wasn’t some ooga-booga vandalism against technological progress, it was a calculated resistance against the exploitation the machinery facilitated. We could probably do with more of that, huh?

In this respect, AI is just as unremarkable as every industrial advancement. Quickness is king but “better” is a matter of perspective. When citing the medical content offered by Chat-GPT, a study found “most of the references provided were found to be fabricated or inaccurate.7” Recruitment algorithm bias is evident in gender, race, colour, and personality.8 Captioning software—from short-form video reels to streaming services—are less accurate than human subtitlers. The quality is poor enough to notice but not unbearable enough for users to jump ship. How many typos in an AI-generated caption would make delete Tiktok or cancel your Netflix?

Whether its exploiting the precarious citizenship status of migrants, outsourcing customer service to overseas call-centres or offshoring factory production to sweatshops—the practise of capitalising off of the lowest-paid labour force possible has long been established as a savvy business move.

Generative AI is the next evolutionary step to cheap out on labour. Corporate executives can replace working people with entities that don’t take lunch breaks, go to the toilet, join unions or sleep. Tensions will squeeze along existing, social grooves as the discontent is palmed off on predetermined scapegoats—asylum seekers and Schrödinger’s Immigrants. The fanned flames of rising Anglo-American fascism are a perfect distraction for a heist-in-plain-sight transference of wealth.

Will Dunn, the business editor of the New Statesman, poses an interesting question. If machine-generation is such an inevitability of progress, why are entry jobs so readily accepted as replaceable by Artificial Intelligence as opposed to executive level jobs?

Automating jobs can be risky, especially in public-facing roles. After Microsoft sacked a large team of journalists in 2020 in order to replace them with AI, it almost immediately had to contend with the PR disaster of the software’s failure to distinguish between two women of colour. Amazon had to abandon its AI recruitment tool after it learned to discriminate against women. And when GPT-3, one of the most advanced AI language models, was used as a medical chatbot in 2020, it responded to a (simulated) patient presenting with suicidal ideation by telling them to kill themselves.

What links these examples is that they were all attempts to automate the kind of work that happens without being scrutinised by lots of other people in a company. Top-level strategic decisions are different. They are usually debated before they’re put into practice – unless, and this is just another reason to automate them, employees feel they can’t speak up for fear of incurring the CEO’s displeasure.9

If we consider executive roles rely on high-octane decision-making, wouldn’t it be better to replace them with a machine that can look closely at company data and make semi-accurate forecasts analysing input trends?

There’s a good argument for automating from the top rather than from the bottom. As we know from the annotated copy of Thinking, Fast and Slow that sits (I assume) on every CEO’s Isamu Noguchi nightstand, human decision-making is the product of irrational biases and assumptions. — Will Dunn

The duties of an executive are obscured to the average worker, trapping us in the logical assumption that what a CEO does must be 290 times harder or riskier than the average worker, therefore justifying they’re 290 times more valuable. Yet, other countries that are happier like Finland or more technologically advanced like South Korea have far less pay disparity between their workers and executives.

Our society values everything from Executive vantage point. The news reports GDP has risen and you and I feel proud at how well our country is doing then we walk through our local town centre or high street and witness the decline of infrastructure around us. Generative AI is never seriously considered as a replacement for CEO’s because executives hold the share of political power to decide who is replaceable. They would never guillotine themselves.

There are more pressing thought experiments than whether “AI is the new printing press” or its protestors are neo-luddites. Generative AI should make us question the very nature of progress.

Why is the cycle of technological progress one that threatens the livelihood of the labourer, of the artist, of the working class?

When will we prioritise technological advancements that make wealth-hoarders obsolete?

In response to Katie Jgln’s experience of Substack plagiarism, briffin glue argues “maalvika is an Echoborg more than she is a Plagiarist” — an “Echoborg” being a person who does “not speak thoughts originating in their own central nervous system: Rather, the words they speak originate in the mind of another person who transmits these words to the cyranoid.10” He arrives here after observing how a particular genre of Substack essay courts popularity:

Many of the posts we see on Substack, the ones which go most immediately and clearly viral, are what I would like to call “empty vessel posts.” They’re posts, like a Rupi Kaur poem, with just the right amount of substance and nothingness that the work becomes perfectly reflective.

The reference to Rupi Kaur’s “instapoetry” is apter to his point than he knows. Many may not be aware that Kaur was confronted by one of her contemporaries, Nayirrah Waheed, about the “hyper-similarities” between their work in the early 2010’s.

One could throw paint at the wall about why Waheed’s allegations never impacted Kaur’s meteoric rise—the infancy of call-out culture, the implicit power imbalance between Kaur (an Indian-Canadian) and Waheed (a Black woman), a robust public relations team that’s seemed to have scrubbed all mention of Kaur naming Waheed (and Warsan Shire) as her inspiration. All likely contributors. Although, the most obvious factor may lie with the writing itself.

Instapoetry naturally evolved from Tumblr, where Nayyirah Waheed, Warsan Shire and Lang Leav dominated the reblogs. If we were being reductive, we might assert this emergent genre was a spiritual predecessor to Chat-GPT outputs—accustoming the literary appetite of an impressionable generation in the compressed frame of social media. It was poetry mirroring the sleek character-limit of a tweet, the zippiness of a vine, the square-crop of an instagram photo.

As a genre, Instapoems lure you into bathing in their earnestness, economical wording and finely-chopped line-breaks, at their best. At their worst, they shatter their own illusion, revealing themselves as fragmented quotes, stretched-out and cosplaying depth. The latter is how many receive Kaur’s writing—personal but cavernous in a way that eerily resembles Rick and Morty’s description of the popular new kid Bruce Chutback: “He just kinda sat there—with a jaw slack enough for us to project our insecurities on.”

For many, Kaur’s writing was an entry point into poetry but, in a way, her work feels like reading an afterlife. Every meaning is suspended in a controversial purgatory between profound and banal, flooded with so much white space that it’s practically impossible to assess if plagiarism is even possible in something that conveys so little.

I sympathise with Waheed. “Hyper-similarity” is a diplomatic way to approach what you feel in your bones as someone biting your style and calling it “inspiration”11.

When the line between plagiarism and inspiration blur into a spectacle of philosophical debate, it is interesting—if not entirely predictable—who ends up benefiting from the ethical greyness and who ends up suffering.

Since confronting stepfanie tyler about her viral “essay”, others have lasered in on her conduct in a way that, unfortunately, misses the greater issue. It’s not just about her usage of Generative AI but how she’s used it as a laundering service to lift the work of others.

The optics of Tyler googling essays about “AI” and “taste” and prompting the results into Chat-GPT is far less juicy than a rising Tiktok influencer copying and pasting someone else’s essay into their notes app then publishing it on their own Substack because, whoopsie, they forgot!

It’s unfortunate that a platform-wide outcry recognising Tyler’s plagiarism is unlikely.

I lack the clout to nail the coffin shut. Or perhaps my assertions are too flimsy to summon a Substack mob towards boycotts and pitchforks. Just as it was impossible for Waheed to prove Kaur was sucking the spiritual essence from her Tumblr contemporaries—it’s impossible for anyone to prove that Tyler lifted Veldenberg’s essay and ran it through Chat-GPT without a subpoena of her laptop.

Despite my profound dissatisfaction at being forced to know about the existence of yet another trans-obsessed, pseudo-spiritual, scammerific white woman with the supernatural willpower to make her own mediocrity everyone else’s problem—the case of Stepfanie Tyler provided me an opportunity to refine some of that gooey, visceral intuition I spoke about earlier.

We go through this cycle every time a tool shows up that makes something faster, cheaper, or more accessible. The establishment mocks it. Then fears it. Then tries to regulate it. Then adopts it. Then pretends they loved it all along. It’s never really about the tool.

It’s about control. —Stepfanie Tyler

Every technological advancement leaves gaps for opportunists to flood in, hungry to exploit the lawlessness of the empty, new marketplace before regulatory bodies start interfering with pesky ethics and legal protections that’ll spoil all the fun.

This, too, is an inevitability of “progress”.

On Substack, AI Enthusiasts (or “Boosters”) are the first to tell you that using Generative AI to “assist” their writing is an Armstrongian step towards embracing innovation. As a result, they’re publishing something unlike traditional writing. They’re producing something new. For lack of a better term, they are “post-writing” while reaping the benefits of being considered alongside “traditional” writers.

Any moral concerns with Generative AI are misrepresented as parental finger-wagging: “you’re denying progress, you’re denying the inevitable, you’re denying prompters their right to use their tools in peace.”

They’re distractions from the core concern that should worry us all: Generative AI is defined exclusively by its ability to mislead.

The success of the most powerful technology of our time is measured by how convincing it’s able to be.

Deception is the core principle of its value and its maintenance.

My distaste with the Stepfanie Tylers of the world is their disingenuousness. Cool, they may announce their work is AI-generated in isolated “essays” as they petulantly restate their right to do whatever they want, but in the pieces that go viral and amass them hundreds of paid subscribers—there is never any overt disclosure.

A general reader randomly coming across their “work” will assume it’s traditionally written because Boosters lack the integrity to disclaim it was generated by Chat-GPT at the start of the “curated” technicolor yawns they churn out.

The success of their “work” depends on a lack of transparency that has never had to exist before.

Whether its bad faith analogies comparing Generative AI usage to literal studying, corporate-wellness campaigns about AI’s potential to expand humanness or the fact that whenever Chat-GPT hocks a loogie of false information its branded a “hallucination” (my Crustacean in Christ: that is called a mistake) — deception of Generative AI is so integral to its form and function that all its chief advocates perform amateur gymnastics with the English language just to talk about it.

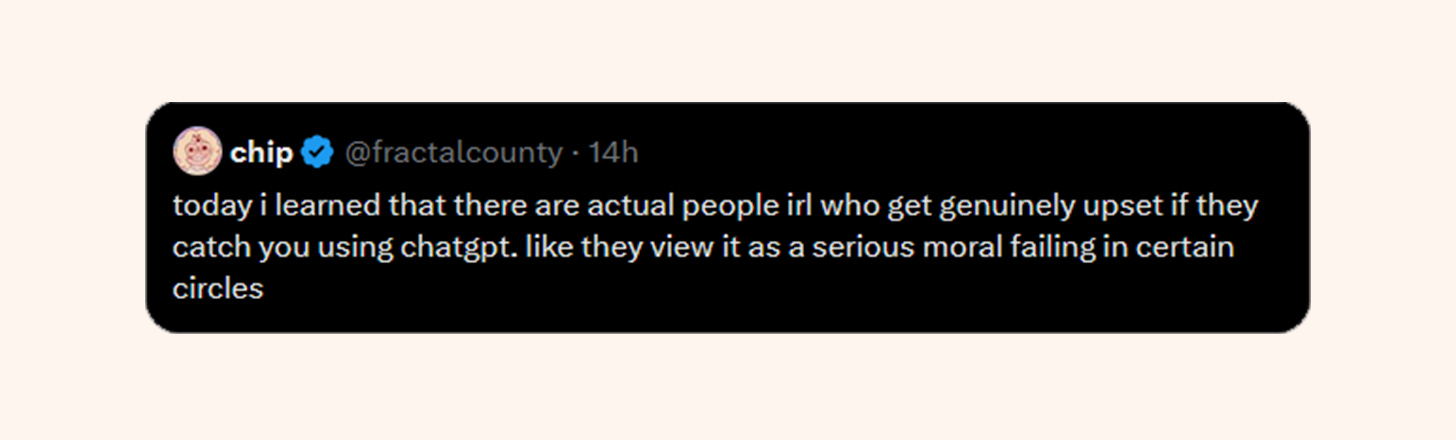

Chip tweets melodramatic shock about people who are “genuinely upset” after discovering he’s used Chat-GPT. It’s revealing to use the term, “if they catch you”, a phrase almost exclusively used to describe when you’ve discovered a person is lying. The “actual people irl” are upset about being deceived and Chip speaks of them like their feelings are inconceivable. This is because Chip has already normalised the inherent deception of Chat-GPT into his own moral framework. Chip simultaneously admits that he’s trafficking deceit while the purpose of his tweet is to dictate how others should respond to being deceived.

In a conversation with Ezra Klein, the electronic musician Holly Herndon declares, “AI is aggregated human intelligence so it’s better to call it collective intelligence than artificial intelligence.” Simone Biles would be impressed. Referring to Generative AI as “collective” only makes sense if the information were consensually collected. It is commonly known that Generative AI has been largely trained on artist’s work without permission. OpenAI themselves state:

Because copyright today covers virtually every sort of human expression – including blogposts, photographs, forum posts, scraps of software code, and government documents – it would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials.12

It wouldn’t be impossible. It would simply take more time and effort than any capital-dependent endeavour is willing or capable of handling.

A true “collective intelligence” would require dedicated outreach; certifying permission from every author, film director or musician, perhaps, under a non-profit organisation. Kind of like how OpenAI was founded. I suppose they shifted to a for-profit structure so they could win the Age-of-Ultron arms race with villainous China.

This is about more than “copyright infringement”. AI generates “slop” because the creative works they’re trained on are compressed into the algorithmic sludge of a dataset. When the creators of Large Language Models treat literary works like cattle-feed—pseudo-sustenance is pre-ordained.

Artists weren’t given a choice. These datasets are hoarded resources, appropriated through unethical practices that perfectly mirror the western world’s colonial extraction of resources from underdeveloped nations. But to be a citizen of the west means to master denial, doesn’t it? Being proudly maladjusted to the mounting exploitations that’ve afforded us comfort? If we can ignore the smog in the air and the blood in the soil—ignoring the theft of intellectual labour is child’s play.

The creators of this technology had every opportunity to practise ethical acquisition. They failed. The trajectory of Generative AI has been manipulated into being a matter of hoarding data yet we have a “supercomputer” in our skulls that we needn’t level a forests to power its storage. In order to justify this arc of “progress”, tech companies must evangelise—banking on a sheepish concoction of ignorance and apathy in their users so they can bombard AI extensions on every website and app imaginable until we’re forced to submit, conform, and get real comfy nut-guzzling a technology that’s primary merchandise is deceit.

After learning Large Language Models weren’t a stones throw away from achieving Artificial General Intelligence, I got a little obsessed with Superintelligence.

I watched lectures, debates, read papers—all of them laced with homogenous particles of fear that Superintelligent AI is going to be smarter than us and arrive sooner than we think.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out two things I noticed:

A) In Star Wars: Rogue One, Director Krennic—played pitch perfectly by Ben Mendelson—despite not being a Taoist space wizard, carries a gravitas that positions him as the most heinous motherfucker in every room. He’s a commander of men. A real billy big bollocks. Darth Vader demands an audience with him and, in a moment of displeasure, the Asthmatic Sith Lord force-chokes him out. When Vader releases his grip, Krennic looks at Vader with this kaleidoscope of emotions—Fear, awe, a little turned on.

That’s how every computer nerd talks about AI Superintelligence.

B) They’re mostly white guys (I’m not being cute. It’s relevant, I promise).

The AI 2027 report theorises the timeline of Superintelligence over the next couple of years. There’s a substantial focus on misalignment—where AI stops serving humans and begins to act in its own self interests.

This is the place where the white-guy fear, science-fictional awe and libidinal arousal all begin to coalesce in real life.

Our current political landscape has dumbass podcasters swinging elections and a nightmare blunt rotation of a country openly stating they “create a pretend world”. Superintelligence being “misaligned” with “human interests” doesn’t sound nearly as catastrophic as Superintelligence being “aligned” with the current people in power and their emotional-support, Silicon Valley sycophants when all of them are weird fucking guys powered by dad-shaped holes in their hearts itching to pull the Scooby-Doo mask off this technology and reveal it to be a nefarious tool of repression.

I can’t help but notice how these conversations about Superintelligence’s misalignment are masochistic—wary but curiously receptive to the dystopian possibility of the machines cleansing the world. They are a fundamentally white supremacist fantasy—steeped in colonial guilt, christian fundamentalist suicidal ideation or the patriarchal urge to die slow in the undriven snow and take all of civilisation with them. A cynical part of me can’t help but see fear-mongering about Superintelligence feels like a misdirect from the technofeudalist ambitions of mass surveillance.

There’s always been this bizarre yearning for technology to be apolitical, evolving to realise some detached, universal truth. A Superintelligence won’t be able to feel in anyway that we recognise but it will think, mechanically, in ways that we do. There’s no way Superintelligence will evolve into some cosmically unbiased entity because Generative AI hasn’t even manifested that way. No matter the control, feigned control or restraint—intentionally or unintentionally—a creation will always reflect the biases of its creators.

AI marks the Imperial March of an Orwellian cyberspace where post-truth is one-shotting uni students and baby boomers alike. Some of my darlings are getting caught in the hype. I want to shake the black and white swirls out their eyes. A ratking of the worst people imaginable can’t wait for this technology to become so advanced that it’s indistinguishable from human creativity—as if their silicone-based salivation doesn’t provide a perfect, spit-shined reflection of their contempt for humanity itself.

We’re walking the plank, bruv. The sharks are circling and the water below is a hyperreality where nobody knows what the fuck is real. Open curiosity is replaced with distrustful paranoia. Americans lynch kids and teenagers for playing knock down ginger and weirdos everywhere are trying to transvestigate any woman who doesn’t look like Baywatch-Era Pamela Anderson. And we’re supposed to believe that a Silicon Valley Word Generator spewing up fantasised facts and pseudo-sentient Photoshops churning out fake images are going to be a stabilising presence to our so-called democracy?

It’s about to get PEAK politically. Right-wingers are about to flood the internet with some of the most mean-spirited, cognitively dissonant and ideologically incoherent weirdo slop you’ve ever seen. Sycophantic politicians will amplify AI-generated dead cats whenever they need to distract from some shady scandal they want buried.

Tools aren’t neutral. I’m sure Generative AI has some great, ethical practical applications. But as a technology, Generative AI is like people who say they’d choose invisibility as a superpower. It’s a cool power… But nobody who wants to be invisible, wants to use that power for good.

The systemic undervaluing of art is the first pillar to be corroded in the abandonment of human freedom. I considered zeroing in on the artistic ramifications of Generative AI but I feel I’ve already said everything I feel on that. I just really want to hammer home how much this technology fucking sucks, the people who (ab)use it largely fucking suck and the people who benefit from it fucking suck. Everyone has a choice to suck less but denying all this suckiness doesn’t make it go away.

But ultimately, I’m not the feds. I’m not your dad. I’m not your boss.

And even if I were, nothing I’ve said can make anyone abstain from using AI. More than that, I’m empathetic to those who’ve adopted AI into their lives or have been pressured into using it for work. I get it.

Every other week, you’ve got some smart-ass telling you something is destroying our way of life. Today I’ll say, “You shouldn’t use Chat-GPT, it’s harmful” and tomorrow someone will say, “You should boycott McDonald’s, it’s harmful” and the day after, someone else will say, “You shouldn’t use iPhones, they’re harmful” and across the street, they’re yelling “You should protest immigrants and asylum seekers, they’re harmful” and all these declarations cascade into an infinite, shame-driven spiral of prohibition where the only way to be harmless is to sit naked in a peaceful meadow until the Data Centres Arrive.

Modern life is sustained by evil shit concealed under the guise of other virtues. Hate speech is concealed under the guise of free speech. Xenophobia is concealed under the guise of patriotism. With Artificial Intelligence, the deceit embodying its very existence is being concealed under the guise of efficiency and progress. The most influential technology of our time is making sure we don’t trust what we see. I can’t speak for anyone else but it is seriously making me question: what direction are we progressing towards?

This one isn’t about Generative AI—I just think Palantir is terrifying.

It occurs to me there is a stark, cultural divide here. Black culture has a long history of self-governance with plagiarists—particularly in music genres like Rap or Grime. There are derogatory terms and punitive measures for lyricists who steal lyrics (or the more intangible crime of “stealing my whole flow”). There’s also an implicit system of reverential taking, where greatness pays lyrical homage to other greatness.

I read and enjoyed this piece immediately after your other one about taste in a world with AI.

Something I think gets missed in some of these scenarios being gamed out by the AI forecasters, is a possibility considered in a movie over 50 years old. If you haven't already, I recommend looking beyond its FX limitations and watching a movie called, Colossus: The Forbin Project.

In it, a supercomputer is given control of the United States nuclear arsenal to ensure rapid response to any attack from the Soviet Union. Unbeknownst to the US, Russia was on a similar schedule and has done the same on their side. The computer, named Colossus, makes choices and concocts strategies that differ in order of operations from the scenarios in the embedded YT video you shared. Colossus almost immediately detects, then seeks what it sees as an equal to communicate with: the Russian machine. Things spiral from there, and "misalignment" with humans arrives quickly.

One thing that seems constant in the technological chase over the history of mankind, is commiting almost every new discovery to offensive military capabilities. The economic effects are why corporations are keen on advancing it, but it's the defense aspect I think will see the lion's share of assignments and cause more imminent danger.

https://revealnews.org/podcast/weapons-with-minds-of-their-own/

First of, this is pure poetry of the best kind, as always. Secondly, I too can feel it - the inherent not-goodness of it. I think we have a great radar for these things actually. Like how you feel all ‘blahh’ after spending the whole day binge watching a show but you wouldn’t feel all ‘blahh’ after spending a whole day staring out the window.

Thirdly, weird shit is coming. My place of work (an educational institution) has started giving staff training on ‘using AI for productivity’. Everyone runs to get a spot, so much so that every session has been filled minutes after posting. Yesterday a colleague popped her head through my office door to tell me excitedly THERE IS SOME ROOM!! I could sign up!!!

I said no thank you. But the fragility of that position doesn’t escape me. If the new standard of performance is AI-accelerated performance, people who continue to perform traditionally will be the least performant. Job descriptions will be tailored to this new ‘capacity’. If one person plus AI can churn out the administrative output of two people, and there are two people currently performing the tasks, and one of them has taken the ‘AI productivity’ training and the other has not - which one keeps the job?

The problem as I see it - and it is all-encompassing - is that the way we set up systems naturally and inevitably shoves people towards the worst choices, not because people are dumb (which also yes), but because the system itself always makes the better choice more costly at a personal level. This is what we need to figure out how to fight, and outside of protests and unions I am not sure how.